After decades of prohibition and stigmatisation, psychedelics have emerged as a promising treatment for those with mental health conditions.

On the 3rd of February 2023, Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration approved the prescribing of MDMA and psilocybin for the treatment of mental health conditions. Prescribing will be limited to psychiatrists working with patients in a controlled medical setting.

- MDMA, the active ingredient in party drugs such as ecstasy, will be able to be prescribed to some patients experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

- Psilocybin, a compound found in psychotropic “magic” mushrooms, will be listed as medicine for treatment-resistant depression.

The approval of psychedelics for medicinal therapy in Australia marks a significant shift in the way we think about and approach mental health treatment.

But how did this all come about?

A new treatment for mental health disorders

Statistics indicated that in 2017 over 970 million individuals – that’s over 13% of the global population – had a mental health or substance use disorder. Following the COVID-19 pandemic, this number is likely more.

Shifting the focus to improving treatment options for mental health disorders has become increasingly urgent.

In the wake of this mental health crisis there has been a resurgence of interest in the therapeutic potential of psychedelic drugs, including the “classic” psychedelics:

- Psilocybin – the active component of magic mushrooms.

- DMT – the psychoactive constituent of the ceremonial brew ayahuasca, mescaline, and LSD.

- Empathogens, i.e., MDMA “ecstasy”.

Research into psychedelics has shown promising results

While psychedelic research was popular in the 1950s, the sanctioning of psychedelic drugs in the U.S. and Europe in the 1960s and 1970s restricted research.

However, accumulating evidence of the mental health benefits of just one or two doses of psychedelics paired with psychotherapy has bolstered enthusiasm among scientists, clinicians, and the public. The regimen contrasts starkly with the daily dosing regimen of existing drugs like antidepressants.

Promising evidence from recent clinical studies shows that psilocybin, which is broken down in the body into the active chemical psilocin, may not only rapidly relieve depression symptoms, but the antidepressant effects could last for at least a year.

The benefits of psilocybin administered in a safe, therapeutic setting, have also been seen in alcohol use disorder, nicotine addiction and end-of-life anxiety in terminally ill patients.

“Many people describe psychedelic experiences as profoundly meaningful, which may help them develop a sense of purpose in life or envisage an alternative to being stuck in a rut with alcohol.”

Professor David Nutt

How do psychedelics affect the brain?

The name ‘psychedelic’ was coined by Humphrey Osmond in 1957 derived from the Greek words ‘psyche’ – mind, and ‘delein’ – manifest.

“Psychedelics are powerful psychoactive substances that alter perception and mood”

Professor David Nichols

Psychedelic drugs have similar chemical structures to the neurotransmitter serotonin, which regulates mood and emotions.

Antidepressant drugs like selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) increase levels of serotonin in the brain in a non-specific manner. However, it is the precise ability of psychedelics to activate a particular serotonin receptor, the 2A subtype (5-HT2A), on neurons (brain cells) that is thought to initiate their psychedelic – and therapeutic – effects.

Dense concentrations of 5-HT2A receptors are located in brain regions essential for cognitive processing, behavioural control and memory – particularly the frontal cortex.

The activation of 5-HT2A receptors by psychedelics leads to more than just shifts in states of consciousness and perception – multiple signalling pathways within neurons become activated, leading to long-lasting changes in neuron structure and function – a process called neuroplasticity.

Psychedelics promote neuroplasticity

Depression and PTSD have been linked to the loss of connections (synapses) between neurons in the frontal cortex, indicating reduced neuroplasticity.

Experimental administration of psychedelics in rats and in people quickly boosts levels of BDNF (brain-derived neurotrophic factor), a key chemical involved in neuroplasticity.

The rapid and lasting therapeutic effects of psychedelics in mental health disorders may be due to their ability to enhance or restore neuroplasticity, particularly where reduced cognitive flexibility and ruminating negative thought patterns underlie symptoms.

By helping to rewire the brain, individuals adapt to new thinking patterns and behaviours that benefit their mental health.

Making and breaking connections in the brain

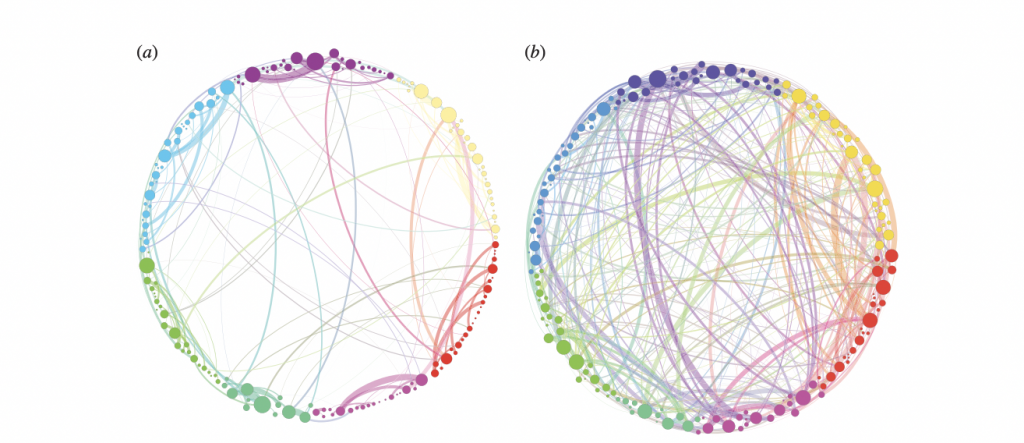

Functional brain imaging techniques have revealed how psychedelics can change brain activity and connectivity.

In one study, volunteers took LSD and then underwent functional brain scans that measured changes in blood flow and neural activity. During the LSD trip, neuroimaging showed that the network connections became adaptable and more plastic.

Interestingly, LSD also promoted connections between brain regions that don’t normally communicate with each other.

A clinical study with psilocybin therapy in patients with treatment-resistant depression showed a similar brain network organisation plasticity. In these patients, the antidepressant response to psilocybin was associated with inflexible brain connections becoming more interconnected and adaptable after treatment.

Sculpting brain cells with psychedelics

While patients report the benefits of psychedelics on mental health, scientists have used detailed imaging techniques to examine the effects of psychedelics on neurons.

A study in mice found psilocybin changed the structure of dendritic spines. Dendritic spines are tiny protrusions from dendrites, which form synapses with neighbouring neurons. In mice that received psilocybin, the size and number of dendritic spines in the frontal cortex increased by about 10% within one day. And the new spines were still present a month later.

The formation of new neural connections is a critical element of brain plasticity processes. It is conceivable that boosting neuroplasticity with psychedelics primes the brain to learn and adapt during subsequent therapy sessions.

Rebuilding the brain: better and stronger

The capacity of psychedelics to induce neuroplasticity led to the researcher Dr David Olson coining the term “psychoplastogen” to describe the rapidly promoted flexibility in the brain.

Beyond changing the structure of neurons, researchers showed that the administration of DMT in rats led to increased neurogenesis – the birth of new neurons – in the hippocampus, a key brain region for memory. Rats treated with DMT had improved memories too, indicating that psychedelics could potentially improve cognitive function.

Studies have also shown that psychedelics increased resilience to stress, potentially lowering the chances of symptoms relapsing after psychedelic therapy.

Regulatory approval of psychedelic drugs in Australia

Australia is now the first country in the world to approve psychedelics as a medicinal treatment.

But there are currently no approved medicines that contain either MDMA or psilocybin in Australia. That means authorised psychiatrists currently will need to source unapproved medicine that contains these substances for patients.

There have also been some reservations about prescription psychedelics, with some clinicians believing the move is premature.

Nevertheless, the announcement has provided new hope to individuals with mental health disorders who haven’t responded to treatment. About one in three people with depression don’t respond to standard pharmaceutical and psychological treatments.

Potential uses in the clinic beyond psychiatry

In tandem with rising cases of mental health disorders, neurodegenerative disorders like Alzheimer’s disease are also increasing globally with an ageing population. Scientists have started to investigate how the plasticity-promoting potential of psychedelics could protect the brain, increase new neurons or potentially rewire connections to slow or even prevent cognitive decline.

Harnessing psychedelics’ regenerative effects has led to the investigation of whether psychedelics can heal brain damage from stroke.

The future of psychedelic drugs

The development of psychedelic drugs may usher in the next generation of psychiatry and neurology treatments.

Clinical trials with psychedelics so far have been encouraging, but as of yet psychedelic therapy has not reached medical approval. Psychedelic trials are difficult to run, particularly as those enrolled have high expectations that could bias reported effectiveness.

But the elephant in the room that could limit people’s willingness to use psychedelics is their very nature as hallucinogens. Although many rate psychedelic trips as some of the most meaningful experiences of their lives, there is still a stigma associated with psychedelic use.

Could taking the trip out of psychedelic drugs still retain their therapeutic effectiveness?

Initial studies with mice suggest yes, and these “non-hallucinogenic psychedelics” might open doors to new therapy programs and further increase their acceptance.

About the author.

Dr Amy Reichelt is a passionate psychedelic drug development professional. She serves as a board member at the Women in Psychedelics Network and holds a PhD in Neuroscience (Cardiff University), and is recognized as a leader in cognitive neuroscience, nutrition neurobiology and behavioural pharmacology.

Share the love

[Sassy_Social_Share]

About Dr Sarah

Neuroscientist, Author, Speaker, Director of The Neuroscience Academy suite of professional training programs.

Latest Posts

Free 10 day micro-training in neuroscience

Learn one neuroscience concept a day!

10 simple, bite-sized lessons in brain health, delivered daily to your inbox